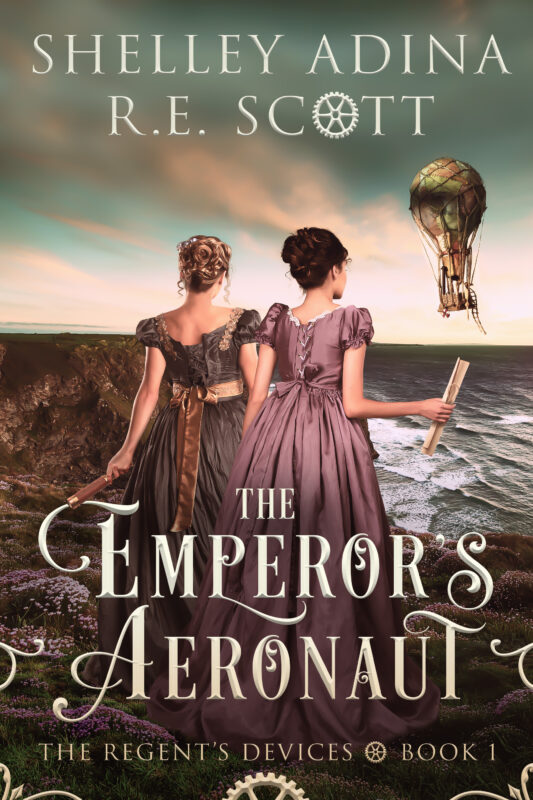

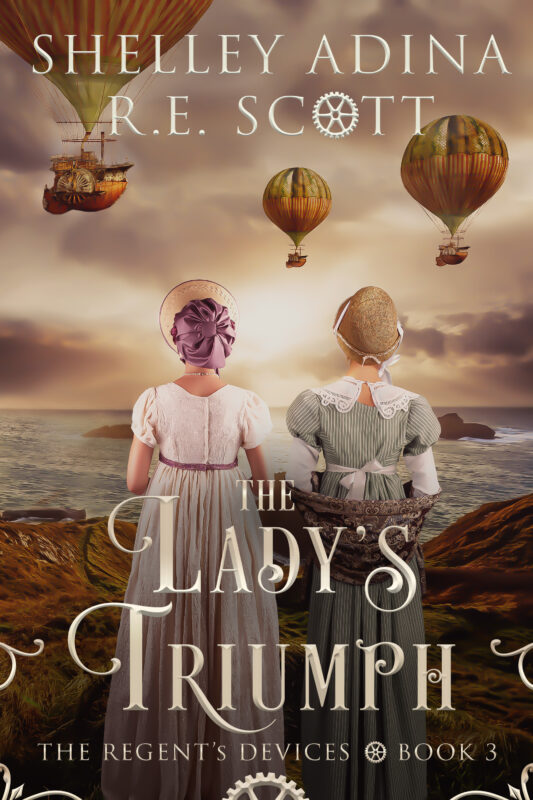

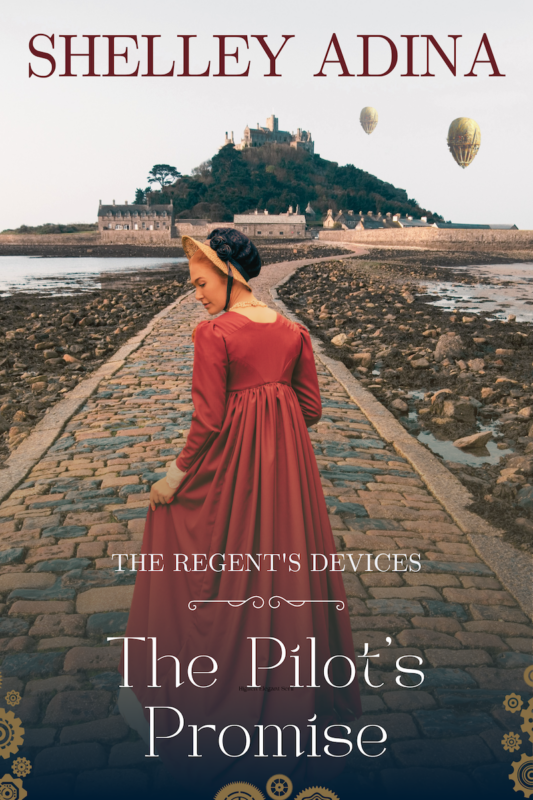

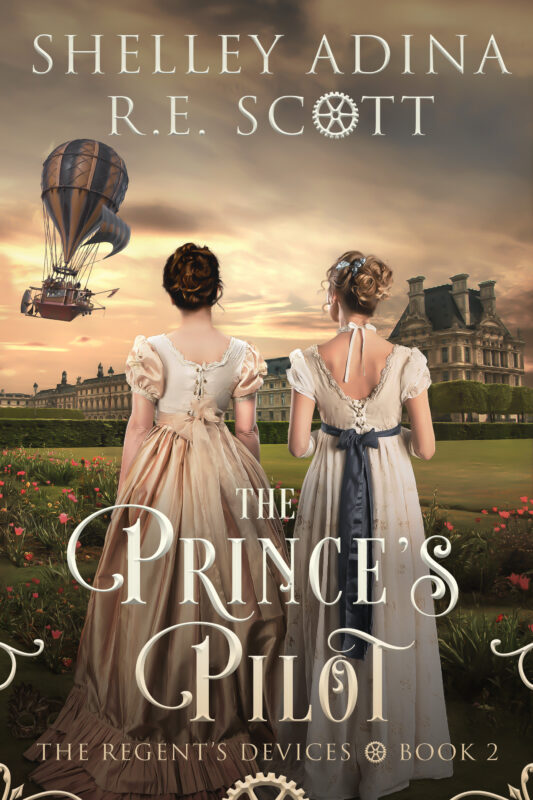

The Regent's Devices • Book 2

Napoleon’s invasion of England is hidden in the clouds…

It is 1819, and Cornwall is agog at the daring of the two young lady aeronauts who, earlier in the summer, flew nearly to France and back in their homemade air ship. Much more is riding on Loveday Penhale and Celeste Blanchard’s new and improved vessel—they plan to win the Tinkering Prince’s prize, offered to anyone who can help England win the war against Napoleon.

To their dismay, they must take two local gentlemen aloft to report on the ship’s capabilities. While Captain Trevelyan and Emory Thorndyke are welcome in drawing room and ballroom, their presence on the air ship proves disastrous. Wildly off course, Loveday barely manages to bring the vessel down safely—in France! Now it is up to the gentlemen to keep the newly designed ship hidden while Loveday and Celeste secure supplies for its repair from Celeste’s former home, l’Ecole des Aéronautes in far-off Paris.

But much has changed since Celeste left the capital, and enemies lurk in its very walls. With her famous aeronaut mother dead in suspicious circumstances, and the flight school closed, there is only one thing to do—make up a story about her absence and approach Napoleon himself. He promptly makes Celeste his Chief Air Minister, and commands her to plan the invasion of England by air. Can she and Loveday stay alive in this nest of vipers long enough to help their stranded friends? Before they are unmasked as spies—and before their beautiful air ship is captured and used to attack England...

Chapter 1

© 2022 Shelley Adina and R.E. Scott

Truro, Cornwall — Late August 1819

Is there anything else I might do to assist you, Loveday?”

Such a civil inquiry to be made in such a roar, but this was red-bearded, irascible Thomas Trevithick, who had probably proposed to his wife at the same volume.

“Thank you, Thomas, but no,” Loveday Penhale said over the ringing of Rudolph Clement’s hammer as he battled a sheet of copper. “This small boiler is even better than our last one, thanks to you and your men here. Now that we have installed it in the gondola, I believe we may call it complete.”

What a change three months had wrought—free rein at the steam works for herself and her friend Celeste Blanchard, actual civilities falling from Thomas’s lips instead of criticisms, and tolerance of their presence that was now almost cordial.

It was as great a miracle as finding lifting gas in the depths of the Cornish bedrock.

“Aye, it’s a fine bit of work,” he agreed. “Better this be done in the full light of day, and not cobbled together with bits and bobs and hope.”

“We still have hope,” she reminded him with a grin. “That did not wind up in the sea in the spring, at any rate.”

He hesitated, his ham-sized hands pushed into the pockets of his leather apron. “Tez glad I am, Loveday, that you made landfall on your own doorstep. It would have been a sad loss to us all if you’d gone down with your air ship.” His face turned even more scarlet than usual. It looked almost painful.

She resisted the urge to pat his shoulder, for that would have embarrassed them both to no end. “We will not distress ourselves with the might-have-beens,” she said bracingly. “Come, tell me what you think of my work on this narrow-gauge copper piping.”

Relieved, he bent to inspect it, and they returned to a congenial discussion of hydraulics and pressure. Celeste sent her a commiserating smile from where she was inspecting the installation of the steam engine.

Yes, how far they had come in every part of their lives since May! For once the original Lark had been launched and her remains subsequently washed ashore near the St Mawes harbor—truly, there must be some reason why the tides so consistently brought in large floating objects that she and Celeste had misplaced—there was no keeping secret any longer what the two of them meant to do.

Compete for the Prince’s prize. And win.

She and Celeste were young and unmarried. Neither of them were permitted to attend a university to take a degree in engineering, like Emory Thorndyke over there at the metal forge. Neither possessed the means to build an air ship, only the imagination and the will.

And yet they had done it.

They’d built it, and flown it nearly to France and back, and lived to tell the tale.

Now, as though the district had been shaken awake by the novelty and sheer nerve of such an endeavor, Loveday and Celeste were suddenly—well, perhaps not the belles of the ball, but certainly the apple of their neighbors’ eyes. Why, even Sir Robert Jermyn, the terribly severe magistrate for Truro who used to frighten Loveday half to death as a child with his beetling eyebrows and abrupt manner, had stopped his landau in the street two days ago to greet her and Celeste as they walked back from visiting their friend, the elderly émigré Madame Racine.

“Good day, Miss Penhale, Miss Aventure,” he had said, lifting his hat.

Loveday curtsied and hoped the two seconds with her head bowed would be enough to wipe the astonishment from her face. And for Celeste to remember she still went by an alias.

“How is that flying vessel of yours coming along?” he boomed.

A pair of women with baskets over their arms had slowed to hear the reply.

“Very well, sir,” Celeste had answered when Loveday could not find her tongue. “We obtained the silk for the new envelope for a very good price, since we could not use the old after its second sea-bathe. Thank you for recommending that mill in Bristol.”

He looked pleased, though the silk was such a revolting shade of brown it was no wonder no lady had wanted to purchase it. They’d had all the bolts for next to nothing, for they could not be particular at this late date.

“And we have had a new gondola built to specifications and have not had to importune our neighbors for their old carriages to be cut up for the purpose,” Celeste went on.

“Capital,” he had said, his face creaking into a smile. “We’ll have that prize, won’t we?”

“I certainly hope so, Sir Robert,” Loveday finally managed. “Though it seems the high-pressure pump built for the mines by the Trevithick Steam Works may give us a run for our money.”

He had nodded sagely. “You have the right of it, Miss Penhale. Either way, we’ll put Cornwall on the map.”

“We will indeed, sir.”

And he had tapped the floor of his landau with his cane to signal his coachman and rolled away, leaving that little word ringing in Loveday’s ears.

We.

Oh, dear. If something went wrong, it would no longer simply reflect badly on her and Celeste. Or even Emory, who had perfected his pump at last.

Their failure would reflect badly on all the county.

But she must not think of that. She had spent far too many hours of her life feeling like a failure. A failure to be graceful and accomplished. A failure to be a good marital prospect. She and Celeste were something else now. Something England had all too rarely seen.

They were aeronauts.

A glow of happiness suffused her that had nothing to do with the sun pouring in the isinglass windows of the workshop. She and Celeste were aeronauts. What other young lady in the country could say the same?

“Miss Penhale, Miss Aventure,” Colin Treloar called from the big double doors of the workshop that faced the street. “The wain’s come for your flying boat.”

“It’s come early! Celeste, we shall have to finish installing the pipes at home.” Thomas and Rudolph were already rolling the overhead pulleys into place to hoist the gondola into the wagon behind the Puffing Jenny.

While Celeste rolled up the pipes in canvas, Loveday hurried over to Colin. “Have them back the wain up to the turntable and we shall have our Jenny deliver it directly.”

“Tisn’t any old them, miss. It’s Captain Trevelyan from Gwynn Place and your Mr Pascoe.”

She tilted her head back as Pascoe, the Penhale stable master, backed the big Percheron borrowed from one of the Jermyn farms so that the wain could receive the gondola. “Captain Trevelyan, I did not expect you today.”

Arthur Trevelyan dismounted a little awkwardly from the vehicle’s bench and bowed once he had reached the ground. “It has been some years since I rode in a wain, I must admit. But the excitement of collecting the gondola was too much to resist.”

“What, no racing curricle?”

“And be thought of as an obstruction in the road compared to the triumphant progress of the new and improved Lark Deux? I think not.” His hazel eyes twinkled, and not for the first time, she marveled at his utter lack of pretension or self-importance. Instead, he entered into the spirit of the thing with the gravity of a man and the enthusiasm of a boy.

The sound of rapid footsteps made them turn. “Vite, Loveday!” Celeste cried, her arms full of canvas-wrapped piping. “Stand aside or you will be run over.”

To put punctuation to her words, the Puffing Jenny let off a gout of steam with a whistling sound that pierced the ears. And here she came, the tiny locomotive engine with the tall stack that was stronger than a brace of oxen. She ran back and forth on her track in the workshop to take heavy equipment to the street. Coupled to her was a flat-bed wagon, on which the gondola had been roped. Their Puffing Jenny was very similar to Richard Trevithick’s original engine, the Catch Me Who Can, built right here in this shop by the great man.

“Oh, but this is exciting,” Celeste whispered. “I can scarcely breathe.”

After all their work, all their revised plans, their dreams were now coming to fruition. No more cut-up carriages for them—the new gondola had been financed by Mr Trevelyan and Loveday’s father, in a humbling show of confidence in their abilities.

Loveday took her arm. “Isn’t it marvelous? Careful, now, the turntable is about to move.”

The Puffing Jenny rolled onto the turntable, and with a jerk and a puff of steam from the engine below the floor, it began to move. When it locked into place, the Jenny now faced back the way it had come, the wagon neatly lined up with the rear of the wain. The pulleys and winch rolled down their track to the door, and their new gondola was lifted onto the wain, to be cradled in a generous bed of straw. How lovely it was—as smooth and sleek as a seashell, its wooden curves gleaming in the sunlight.

Celeste gave a sigh of happiness.

“It is a lovely sight,” Emory said as he walked up, his gaze resting warmly upon her friend.

“It is,” Arthur agreed. “Pascoe, are you sure you trust me with this great beast?”

“His name is Hugo, Sir Robert’s man tells me. It is more a matter of his trusting you, sir, and I believe our journey here made it clear he does. Now, Miss Celeste, if you will step up, I will go back and tie down your vessel.”

With a smile of thanks, Celeste laid the bundle of pipes in the straw and held out her hand to Emory so he might help her up. “We must not keep the captain waiting any longer.”

Pascoe made short work of the ropes, making sure the gondola would not fall over or suffer any damage on the way, though goodness knew the apparatus was sturdy enough that it would take more than a pothole in the road to move it. Sturdy, but light, its form would sail through air more easily than a ship through water. As easily as the lark for which it was named.

Not for nothing had they taken two weeks of unrelenting work to create a scale model of the Lark Deux, right to the silk envelope with its internal corset made of wicker and a second, more durable bladder of treated canvas inside the corset to hold the lifting gas. Each pipe, each tiny control, was created from clock parts and scraps of copper and tin. Even the vanes operated, to control direction and altitude. Loveday had built an engine no bigger than her clenched fist, and when the whole was assembled, Loveday’s family had joined her and Celeste on the lawn to test it.

And it had flown, on the end of an entire spool of Mama’s silk thread, which Loveday subsequently had to spend the evening rewinding. The landing was not quite as successful as they had hoped, and had broken both the bow vanes, but she and Celeste had soon made an adjustment to their placement. When she came in at full size, nothing on the hull would interfere with Lark’s ability to moor or launch, including their mount and dismount.

“Miss Penhale, may I assist you up?” Arthur held out a hand.

Oh, that rascal Pascoe! He had engineered it on purpose so that Celeste would sit on the outside and she in the middle, next to Arthur. But she kept her head high. “Thank you, Captain.” She waved to Thomas and Emory, and they were off.

Somehow, though they had told no one that the gondola would be going home today, word had got out. People stopped in the streets to cheer, and children came to their garden gates to wave as they went by. Even Hugo, Loveday was quite certain, had a livelier step as he pulled a wain as full of hope as it was of their invention through town and out onto the road that led to their village and home.

“I wonder if the Tinkering Prince himself will have such a reception when he rides through town.” Arthur’s voice held laughter.

“I should hope he would have quite a lot more.” Loveday turned to face the front after checking that all was well with Pascoe in the bed of the wain. “I feel equal parts proud and dismayed.”

“What do you mean?” Celeste asked. “For me, it felt quite like old times, when my mother would be cheered in the streets for her latest ascension.”

“But did Madame Blanchard have quite so much riding on her shoulders as we do?”

“Before my flight, she did,” Celeste said soberly. “Every bit as much, and perhaps more. For the villagers and townsfolk here do not have the power to have us imprisoned or even executed for our failure to perform.”

That certainly put her worries in perspective and shrank them to the size of their scale model in comparison.

“Surely you are not losing your nerve now,” Arthur said, glancing at her.

“No indeed. But what if something goes wrong?” Loveday said. “It was bad enough when our hopes went to the bottom of the bay. It seems infinitely worse to think of the hopes of the entire district doing so as well.”

Celeste regarded her, concern in her dark eyes. “This is not like you. What has happened?”

Loveday straightened her shoulders and sat up straight. “Nothing. Perhaps I am simply weary of always hearing that the Prince Regent will come and never actually seeing him arrive.”

“Have you heard nothing, Captain?” Celeste asked, squeezing Loveday’s hand in a gesture of comfort.

“Not a word,” Arthur said. “Not since he was sighted in Lyme Regis earlier in the summer, and we thought he might come to the Midsummer Ball. After that, not a whisper or even a rumor. I suspect he has been called back to London.”

“Perhaps the King has taken a turn for the worse,” Loveday suggested. “Or he must deal with some fresh scandal of the Princess of Wales.”

“It is a shame, whatever the cause,” Arthur went on. “Here is Emory’s steam engine and pump working as well as they are designed to do, emptying the mines of water. Even if powered flight were to come to nothing, at least the mines will be fully operational again by Michaelmas. To the miners, that is worth more than any royal recognition.”

“But the gas must still be removed,” Celeste said. “I hear in a number of drawing rooms much speculation about the mysterious warehouse built by your fathers in St Mawes and the barrels being filled with the gas and stored.”

“The fishermen and miners must think us mad,” he said with a laugh.

“Mama still thinks so,” Loveday said. “She will not even let us say the words lifting gas. Which is difficult, since we must fill our lovely envelope with it, and there it will be, staring her out of countenance upon the lawn.”

“She will change her mind soon enough,” Celeste said. “When we win the Prince’s prize and Mr Penhale and Mr Trevelyan become the richest men on the Cornish coast.”

Hale Head came into view, the promontory that resembled a crouching lion thrusting out into the Channel that had given her family its name, and soon they were turning off on the road that led home.

It was no easy feat lifting the gondola from her comfortable bed and into the place cleared for it in the carriage house. The hay hook was dragooned into bearing pulleys and winch, and with the help of Pascoe and the stable boys, the gondola was guided to its place, where it was held upright with triangle-shaped blocks.

After Arthur had called at the house to give his regards to her parents and then departed, Papa had come out to watch the operation as Loveday and Celeste directed their crew. At length it was completed, and the wain taken back to the Jermyn farm with a promise that Hugo would get an extra ration of oats for his unusual duties that afternoon.

“Thank you for allowing us to complete the final steps in the carriage house, Papa,” Loveday said. “I know it is an inconvenience.”

“I am committed to the project now,” he said with gruff affection. “Besides, with your grandfather’s old coach out of the way, there is plenty of room for it. When do you propose to take her up?”

“Well,” Celeste said, “we must fit the pipes and be sure the engine performs as well as it did in the steam works, and the vanes react as they did in our model. Then we must rig it, fill the gas bags, and finally fit the envelope over all.”

“So, by Christmas, then?” Papa said with a smile.

“No indeed,” Loveday told him, tilting her chin. “Two weeks at most.”

“So soon?” Had he been the sort to wear a pince-nez, it would have fallen off his nose.

“No need to look so amazed,” she said. “The most difficult parts are complete. Oh, Papa,” she said, clasping her hands in delight, “the boatwright has done a masterful job, has he not? Have you ever seen anything so lovely?”

Her father contemplated the gleaming gondola. “Not in the realm of mechanical devices,” he said at last. “But see here, Loveday. This is more important than I think you realize. I believe that if your project is to be taken seriously, it must be witnessed and documented.”

“Our journals have documented each step, sir, down to the screws and nails,” Celeste assured him. “And your entire family witnessed our last ascension.”

“That is not what I mean,” he said. He motioned toward the double doors, and they followed him outside into the sunshine. “I believe that in order for this air ship to be taken as seriously as it deserves, you ought to have someone with you as witness. Like Captain Trevelyan or Mr. Thorndyke. Or both, for that matter, unless this marvelous craft won’t hold more than two.”

“Of course it will,” Loveday blurted, stunned. “But that is not the point! Papa, surely you do not mean we must have an audience.”

“Is our word not enough?” Celeste added. “Why must a gentleman’s observations carry so much more weight than our own?”

“You mistake me, my dears,” Papa said. “No one contests your observations and achievements. In fact, it is all I hear of when I go into the village. But this is your home, where you are known and respected. If these same achievements are recounted in London, it is a simple fact that they will be discounted on hearing, simply because you are young and female.”

Celeste said something in French that Loveday was quite certain should never be expressed in polite company. Whatever it was, it could not do justice to her own feelings at this moment. It was a very lucky thing that the crowbar was inside the carriage house, for she wanted to hit something—or at the very least, throw it.

“I can see you boiling over, maidey, like your own steam engine,” her father said mildly. “But apply that brain of yours to what I have said, and you will see the truth of it, right or wrong. I shall call on the captain and Mr. Thorndyke with all dispatch. I would trust none other but those two with such a challenge—and such a privilege. For the ship will carry precious cargo indeed.” With a smile, he left them simmering.